The silver-rimmed glasses appear to rise each time Shelley Wong is happy.

Wong of Choctaw, is happy a lot while working her farmers market tables along the west edge of the Oklahoma Department of Agriculture, Food and Forestry (ODAFF) parking lot.

The produce under the blue canopy sun tent – butternut squash flanking her to the left and golf ball sized red onions to the right as well as the Chinese okra and the bitter melons before her – are a source of pride because each is from her garden.

A customer studies the items on the tables and tells Wong, “I’d like these two zucchini.”

Wong smiles, the glasses push up, and she replies, “I picked them myself this morning.”

Later, she goes to the passenger side front seat of the Chevrolet Astro van and grabs an aerial photo to show a visitor.

“Here’s my garden,” she said, the smile kicking in instantly. “It’s maybe 6,000 to 7,000 square feet. There’s my seven rows of the big tomatoes, and this is the little cherry tomatoes. Over here is the broccoli, and here I plant spaghetti squash.”

Across Oklahoma, there are dozens of registered farmers markets that are essential outlets for agricultural producers in providing opportunities for them to meet the consumer demand for locally grown, fresh produce. Farmers markets also provide opportunities to create strong community ties and a link between rural and urban populations by allowing farmers and consumers to interact.

Just over the produce and behind the tables stand those who raise a quality product and want to see the public enjoy it. Many of those individuals have interesting stories, including Shelley Wong.

She remembers

The painful cries of a baby.

The moaning of a senior adult.

Many have said that food is taken for granted. Not by Wong.

When Wong – Wong Moy, Shuet Fong – tells the story of her childhood, the happiness is nowhere to be seen. One is certain the glasses on her cheeks will soon begin catching tears.

Food is personal, and that feeling traces back to those babies and seniors, she said.

On Oct. 1, 1949, communist revolutionary Mao Zedong officially proclaimed the existence of the People’s Republic of China, naming himself head of state. Wong was only 3 years old.

She grew up in a time of a “government rate” for food. In her village, that was about 20 pounds of rice per person, per month. That was for two meals a day. Those who couldn’t work, like a child or an older adult, received less, she said.

Wong’s father died when she was 6, and she was the middle of five children. However, her grandfather and an aunt in New York sent them money, so they had a better situation than some others. Still, Wong saw and heard the impacts of hunger all around her.

“So some kids, they cry all day, all night, and some older people,” said Wong, 71. “They swell up because they don’t have enough food.”

She felt she had to get out.

It was 1962. Wong’s grandmother Yee Lau Kwai needed to take a trip and couldn’t see well, so she needed, as was approved by the government, a child 12 years or younger, for assistance. Here’s the catch: Wong was 16, but didn’t have a birth certificate and was shorter than her present height of 4-feet, 11 inches. So they listed her as 12 and she received a passport. They went first to Macau on the south coast of China, across the Pearl River Delta from Hong Kong.

“I lived in Macau for a month and a half and then got into a small boat and we sneak into Hong Kong,” Wong said. “At that time it belonged to the British.”

It was in Hong Kong, in late 1964, she met Sheldon Wong, who had returned to China from Los Angeles to find a wife. They were engaged in March 1965 and married in May of the same year, and in September traveled to Los Angeles, where Sheldon had a grocery store.

“Not long after, we got robbed,” she said. “Four guys come in and they shoot our roof, we got scared so we moved out from that business and sold his part to his brother.”

In 1969, Shelley became a U.S. citizen and shortly thereafter, the Wongs moved to San Diego, where they opened a restaurant that seated about 70 people and served Cantonese cuisine. That continued for about 15 years until Sheldon had health issues and they sold. After a while, Shelley started the restaurant again, in a mall.

Food obviously plays a role in everyone’s life, but it has played a significant part in Shelley’s life: the grocery store, the restaurants, the garden and the farmers market.

“We pay it back a lot of time,” she said, and then explains. “A lot of time at the restaurants, we would have people come in and they say, ‘We hungry, can we have some food?’ and we always give them some fried rice. If they are hungry, we are willing to help them.”

Shelley and Sheldon also sent money back to family members in China and through the years, some family members moved to the United States. Also, her grandmother initially stayed in Hong Kong and then moved to the United States. The grandmother lived with the Wongs until the early 1980s and then moved in with other family members in California.

Wong did return to China to visit, making the first of five trips starting in 1982.

In Oklahoma

While visiting their son and daughter-in-law in Oklahoma, they started thinking about making the move from California and did so in October 2005, buying a house in Midwest City.

It was July of the next year that they moved into their new home in Choctaw.

She saw food – well, sort of.

“When I move into the new house, my yard is pretty big,” Wong said. “I start a couple of rows and I plant those bitter melons, because I love them.”

This was her introduction into soil farming.

“I like to see the things growing from a seed,” she said. “You go out there and you see them popping up. I help them grow and I feel very proud of myself.”

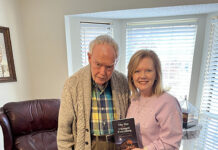

In addition to produce, Wong loves people. That’s why the garden has led to another perfect fit for her, farmers markets. She, along with Sheldon, 87, attends one in Choctaw and the one at the ODAFF parking lot in Oklahoma City.

At the latter, a customer walks up and lifts one of the Chinese okra from a tray.

“I bought one a couple of weeks ago from Shelley and I was like, ‘That was really good,’” the customer said. “I just stir fried it, and it was really pretty tasty.”

Wong’s happiness is readily apparent.

“In my life, I was in business all the time,” Wong said. “I have good communication with the people, with the customer.”

And about that time another walks up and spots her onions.

She grabs a yellow plastic hamburger basket, and scoops some up. Wong grabs an Oklahoma Grown bag, and the woman dumps the onions.

What does she use the onions in?

“Everything,” the customer said. “I had a roommate once that asked me if I made a meal without onion. Pretty much, it doesn’t happen.”

Wong seconds the motion.

“I put onion in soup, stir fry…,” she said. “I love them too.”

Wong then ties a knot in the top of the bag and hands it over, not only thankful for the sale, but the conversation and the fact that someone wants what she has personally grown in her Oklahoma garden.