Story and photos by Darl DeVault, contributing editor

Born on a cotton farm near Bessie, Oklahoma, Ivan Evans Jr. married his Dill High School sweetheart Erma J. Sallee and was drafted right after graduation to become a decorated infantryman in the U.S. Army during the last year of WWII in Europe.

After only 16 weeks of U.S. Army basic training in Texas, he sailed as a replacement soldier to rainy, fierce fighting in early November in the rugged forested terrain of the French Vosges Mountains. The mountains served as a seemingly impregnable fortress for German troops determined to hold the last barrier between the Allies and the Rhine.

Trained quickly to be a replacement soldier in the infantry because seven out of ten infantry soldiers suffered casualties in WWII, Evans became a light machine gunner.

Evans, now 98 and a 23-year resident of Spanish Cove Retirement Center in Yukon, saw more action in his almost year on the front lines in Europe than many in the whole war. He is proud that his fellow Spanish Cove residents celebrate and honor American veterans for “their patriotism, love of country, and willingness to serve and sacrifice for the common good.”

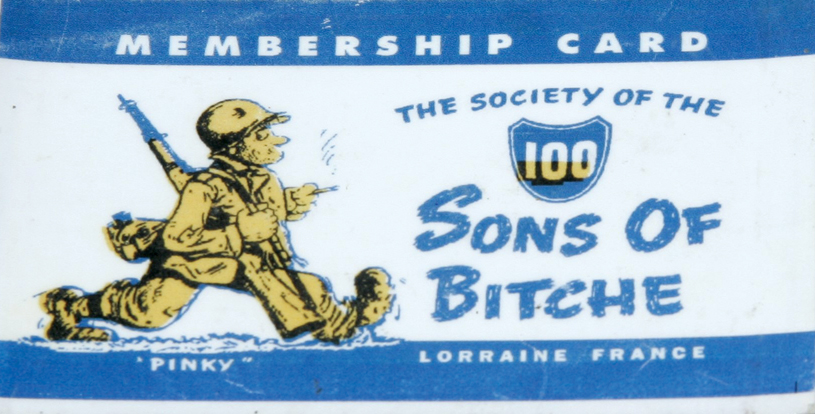

He paid careful attention in his abbreviated training, earning a Bronze Star for gallantry and a Purple Heart as his proud 100th Infantry Division conquered more enemy territory with fewer casualties than any other division in the war.

“About my Purple Heart, a German did that—nothing I could do about it,” Evans said in a recent interview about the fierce fighting taking the Maginot Line.

The only time Evans was not at his light machine gun on the front lines attacking was the seven weeks in a Mobile Army Surgical Hospital unit and recovery from being shot in the arm.

He explains his complete recovery was based on luck as he was moving through triage waiting for surgery when it was the only neurosurgeon on duty’s turn. So, Evans received the most skilled surgery available to repair the damaged nerves in his arm and ensure he was pain-free and capable for the rest of his life.

His full recovery meant soon he was back in the line, earning more respect from his fellow soldiers in his platoon.

Evans has now seen 77 Veterans Days honoring his patriotism and service. He is still quick to tell people his survival on fire-swept terrain in WWII was based on mere seconds and inches. He escaped death several times in the world’s largest and most violent armed conflict. Sixteen million American men and women served in uniform during the war. More than 400,000 lost their lives.

His 31-lb Browning 30 caliber light machine gun was a “crew-served weapon.” Evans was the gunner serving with an assistant gunner who carried the tripod and loaded the weapon and two ammo carriers.

Evans spoke about how the 45 caliber M1911 Colt semi-automatic pistol he was issued as a light machine gunner was not enough protection when the fighting got in close. He received permission to carry a M1 carbine rifle.

“My Bronze Star medal was my act of bravery, disarming a German and capturing him in hand-to-hand combat when he attacked me in a bayonet charge while I was in my foxhole,” Evans said. “In the middle of a pitched battle and heavy shelling, I recognized the form of a German soldier appear before me and reached back to grab my carbine lying behind me. So when he thrust his rifle with bayonet affixed at the center of my body, I was turned reaching back, and he just missed me by sliding his weapon across my chest.

I stopped reaching for my carbine and grabbed his rifle before he could pull it back to stab at me again. The force of his forward motion gave me just enough leverage to catch him off balance and turn him as I struck a blow that stripped him of his rifle. In the ensuing hand-to-hand combat, I got control and captured him as my friend in our foxhole did the same to another German. We were both awarded Bronze Star medals for gallantry in capturing these two enemy soldiers.”

Evans returned to wait for the next attack after marching them to the rear to turn in as prisoners. He fought across France and into Germany as part of the 398 Infantry Regiment to the war’s end.

Deep into one of the coldest winters in recent European history, it was often a severe struggle to dig foxholes with smallish entrenching tools through snow and a foot of frozen ground before reaching softer earth.

Evans says once he narrowly escaped death by leaving his foxhole.

“The heavy shelling had just stopped, and the guy in the foxhole with me said the cooks promised to bring up a hot meal,” Evans said. “The guy said I’m going to go get that meal. I said I’m not because the Germans will likely begin shelling again soon. I’m going to stay right here and eat my K ration.”

So the soldier got up and left.

“I don’t remember what made me decide to leave that foxhole after he left,” Evans said. “Soon, I was walking about 75 yards back to get behind our fortified area of the line when I heard a big explosion behind me. I realized it was close to my foxhole, so I ran back, only to find our foxhole was a big shell crater. I had to be reissued all my gear and a new machine gun.”

“And that’s how God took care of me because I wasn’t planning to get out of that foxhole,” Evans said. “I was going to stay there and eat my K ration. God and a promise of a hot meal saved us that day.”

Evans humbly says his performance was typical in the well-disciplined, effective fighting force of the 100th Division taking the battle to the enemy. He said he was proud when it was life and death and surviving as a unit; they all pulled together.

The chaotic fighting to take the strongly fortified Forts Freudenberg. and Schiesseck of the Maginot Line northwest of Bitche, France, from December 17th- 21st, 1944, was some of the fiercest fighting in the war. While farther north, the much-heralded Battle of the Bulge was receiving the lion’s share of the world’s attention.

Evans often moved over open terrain in the leading elements to set up his machine gun to fire on pill boxes under direct enemy observation. These brave men were subjected to artillery, mortar and sniper fire while keeping the assault moving forward.

The 100 Division fought on after liberating Bitche. They fought to cross the Rhine River into Germany, and then battles in crossing the rivers Neckar and Jagst. They attacked Heilbronn to pursue the enemy forces until April 21 near Stuttgart and became a unit in the Army of Occupation of Germany after VE Day restored freedom to Europe. Evans served the reestablished freedom near Stuttgart for seven months after the war.

Evans then returned to his wife in Oklahoma. Together, they attended Oklahoma A&M in Stillwater, now OSU. Evans earned a bachelor’s degree in education, while his wife earned a degree in business education with honors and later a master’s degree in the same subject.

They both taught high school students for the rest of their careers. Evans retired from a 40-year education career as a coach, teacher, and high school principal.

Married almost 69 years, Evans and his wife, who died in 2013, had one son, two grandsons, and three great-grandchildren.

“I wouldn’t be here talking to you if God hadn’t got me through,” Evans said. “I’ve lived a good life. If God were to tell me he’d give me a new life, I wouldn’t take it. I wouldn’t change a thing. I can’t explain how important freedom is; sometimes people do not realize how fortunate they are to have the freedoms they have.”